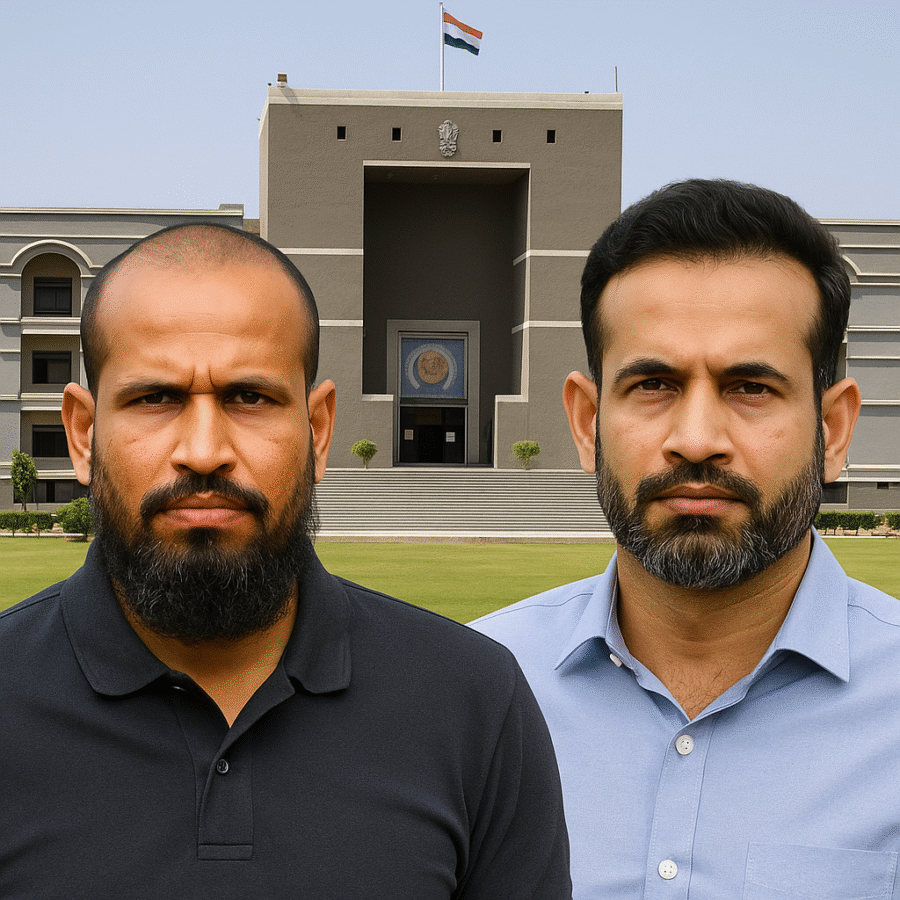

He once cleared the ropes with a flick of the wrist, a powerful swing that sent the ball soaring, winning us a World Cup. Today, that same hero, Yusuf Pathan, finds himself on a different kind of pitch – the courtroom. A Gujarat High Court judge has just called him an “encroacher” and told him, unequivocally, to vacate 978 square metres of prime civic land. No handshakes, no selfies, no second chances here.

How did Yusuf Pathan, a sitting MP and a household name, end up on the wrong side of the law like this? And what does this powerful ruling say to every other influential person watching, wondering if the rules really apply to them? Let’s unpack the timeline, delve into the judgment, and dissect the broader message—because, let’s be honest, this story is way bigger than just cricket.

From Pitch to Politics

Yusuf Pathan’s journey, really, is the stuff of legends. It’s the kind of rags-to-riches tale Indian parents still tell at dinner tables to inspire their kids. Born in Baroda, he rose through the ranks as a power-hitting all-rounder, became an IPL superstar, and famously smashed two crucial sixes that helped seal the 2007 T20 World Cup final for India. He was a force of nature on the field, wasn’t he?

When he finally hung up his boots, that glamour, that public appeal, it didn’t fade. Instead, it seamlessly transitioned into a new arena: politics. We saw the campaign trucks, the garlands, the fervent crowds, and then, a Lok Sabha ticket from the Trinamool Congress in 2024. His victory gave him a brand new badge – Member of Parliament from Baharampur, West Bengal. Back home in Vadodara’s upscale Tandalja neighbourhood, his bungalow already sported a fresh coat of saffron paint, a testament to his rising status. Neighbours often remarked that he smiled more, waved more, and posed for more pictures. Life seemed to be going from strength to strength.

But beneath all the celebratory arches and political fanfare lay a quiet, decade-old headache. Hugging his compound wall was a vacant government plot – just a patch of earth, perhaps no bigger than a tennis court, yet big enough, as it turns out, to drag a national hero into a very public court battle.

The First Wall, 2012

It all began back in 2012. Pathan, then still a cricketing icon, wrote to the Vadodara Municipal Corporation, or VMC, asking to lease this adjacent municipal land for a whopping 99 years. His stated reason? “Family security and privacy,” given his very public celebrity status. The VMC, perhaps eager to accommodate a local hero, prepared a proposal, even fixed a rent. Things seemed to be moving along.

But before the file could even reach Gandhinagar for final approval, something rather curious happened. Pathan’s workers quietly erected a two-foot-high stone wall around the plot. They levelled the ground, laid some temporary tiles. No sanctioned plan, no building permit, just a clear-cut fait accompli. When local reporters dared to ask about this sudden construction, the reply was classic: “We are only demarcating the area we want to lease.” Demarcation or encroachment? Well, that really depends on which side of that wall you’re standing, doesn’t it?

The municipal commissioner at the time chose not to demolish it. The file moved, the months rolled into years, and that wall? It stayed put. Pathan continued scoring political runs, metaphorically speaking, on TV, while this plot, technically, just slipped off the civic radar. It was as if no one wanted to touch it.

Government Says No, 2014

Two years later, in 2014, the state urban development department finally took a hard look at that proposal. And they shot it down. Flat out. Their reasons were clear and unambiguous: there was no public auction, no competitive bidding process, and crucially, the land was actually reserved for a civic utility. The order was unequivocal – reject the allotment.

VMC officials, doing their due diligence, sent the bad news to Pathan’s residence, both by registered post and by hand. Most people, faced with such a clear rejection, would back off, wouldn’t they? But not Yusuf Pathan. Instead of retreating, he reinforced the boundary, planted coconut saplings, parked an old SUV inside, and even installed a tin shed. To casual visitors, it simply looked like a natural extension of his already sprawling garden. To the municipality, however, it was now undeniably a squat.

Yet, still, no eviction notice followed. Critics were quick to allege political timidity on the part of the authorities; supporters, on the other hand, cited “process delays.” Whatever the truth, that wall survived, and with it, a narrative continued to solidify: if you’re famous, if you’re powerful, the rules, it seems, just bend a little.

The Ticking Clock, 2012-2024

Between 2014 and 2024, that contested plot lay cocooned inside private walls, seemingly forgotten. But the city around it was changing, rapidly. This was the era of smart-city tenders, of drone surveys meticulously mapping every inch of urban landscape, of biometric property cards. Encroachment identification wasn’t just about a municipal officer with a clipboard anymore; it went digital. Every single square metre was now mapped and accounted for.

In 2022, a vigilant Right-to-Information activist, someone perhaps tired of seeing public land appropriated, asked the VMC why the plot still showed “under occupation.” The official reply? “Matter sub-judice.” A comforting, if misleading, phrase. Because, as it turned out, there was no court case yet – just a convenient excuse.

By 2024, Pathan had become an MP, complete with a security detail that included Gujarat police and CRPF personnel. The civic body, perhaps finally spurred by the RTI query and the heightened scrutiny around a public figure, finally woke up. They served a show-cause notice, then a clear notice to vacate within 30 days. Pathan’s legal team, naturally, replied. They argued that the boundary existed only for safety, that the land was unused, and that he was willing to pay the market price. When officials didn’t budge, he did what many in his position might do: he challenged the eviction in the Gujarat High Court, claiming “arbitrary action” and “targeted harassment.” The case landed before Justice Mona Bhatt. Suddenly, a decade-old wall became more than just a boundary; it became a crucial test of equality before the law.

The Judgment Day, September 2025

Justice Bhatt’s 22-page order, delivered in September 2025, truly pulls no punches. It’s direct, it’s firm, and it’s a legal mic drop. The key line, the one that’s now echoing across India, states: “Celebrity status or holding public office does not grant immunity from legal obligations.” Powerful, isn’t it?

She meticulously notes that Pathan’s occupation began without any sanction, continued even after a clear rejection from the state government, and absolutely cannot be cured by some post-facto payment. The court wasn’t just making a new rule; it was citing well-established Supreme Court precedent: “Influential persons cannot seek relaxation at the cost of public interest.” This isn’t about one person’s convenience; it’s about the common good.

Procedural objections raised by Pathan’s legal team—like an alleged lack of a proper hearing—were brushed aside with almost dismissive clarity. The judge affirmed that the municipal commissioner is fully empowered to remove unauthorised occupation summarily. And the relief Pathan sought, the regularisation of his possession? That was denied too, precisely because it would “undermine public trust” in the system. Could there be a clearer message?

Justice Bhatt concluded with a stark directive: vacate the plot within four weeks, remove all constructions, and hand the land back to the VMC. If he fails to comply, the civic body is explicitly empowered to use force. Legal eagles across the country are calling it a textbook affirmation of the rule of law. Political rivals, predictably, are calling it long overdue. And fans? Well, they’re just calling it shocking.

Why It Matters

Let’s be clear: this isn’t just about 978 square metres of land in Vadodara. This is about the powerful message it sends to every actor who blocks a beach, every politician who grabs a ridge, every builder who hijacks a public footpath. Courts across India have been flagging “selective leniency” as a creeping threat to sound urban governance for years. When the powerful skirt procedure, the average taxpayer, the ordinary citizen, is the one who ultimately loses out – losing parks, playgrounds, and even basic car parks.

Justice Bhatt’s order isn’t just a judgment; it’s a restoration of a fundamental societal bargain: the bigger your spotlight, the stricter your compliance. MP or commoner, the law simply must look the same for everyone. This verdict also crucially empowers local bodies, those municipal corporations and councils that often buckle under intense VIP pressure. A municipal officer, speaking to The Times of India off the record, summed it up perfectly: “We can now show this judgment when the next celebrity demands favour.” In that sense, Yusuf Pathan’s personal loss becomes a shield, a vital tool, for civic officials everywhere. And for citizens, it’s a rare, refreshing chance to see equality written not just in law books, but in bold, undeniable action.

How the Public Reacted

Unsurprisingly, social media exploded, splitting along expected fault lines. One camp hailed the court’s decision, with comments like, “Finally, land justice!” and “No one is above the law!” Another, equally vocal, blamed what they saw as “Gujarat BJP targeting a TMC MP,” turning a legal matter into a political football. Memes, of course, were swift and merciless, showing Pathan holding a cricket bat on one side, and a court summons on the other.

Closer to home, Baroda residents, perhaps emboldened by the ruling, held a candle-light “Save Open Spaces” march, publicly thanking the unknown RTI applicant who had, years ago, started this whole snowball rolling. Cricket nostalgia took a bit of a hit; fantasy-league handles quietly removed his celebratory clips from their feeds. But a few sober voices also emerged, asking a very pertinent question: would the municipality have acted with such resolve had Pathan remained an ordinary citizen, rather than a celebrity MP?

Transparency watchers suggest the answer might lie in the data. Between 2020 and 2025, the VMC removed 1,312 illegal constructions, but only a mere 38 of those belonged to individuals with celebrity or political tags. That ratio certainly hints at a degree of selective aggression, though it is slowly improving, especially post-drone surveys. Pathan himself has maintained a dignified silence, save for a single, carefully worded tweeted statement: “Respect the law, exploring legal options.” Translation, for those of us who speak legalese: an appeal may very well follow.

What Happens Next

So, what’s next for Yusuf Pathan and that contested plot? Pathan can, of course, file a special leave petition in the Supreme Court within 90 days. His counsel might argue “discretion” or “legitimate expectation,” though, let’s be honest, prospects look pretty slim after Justice Bhatt’s categorical findings. Her judgment was incredibly robust.

If he vacates the land, as ordered, the VMC already has plans: they intend to convert the plot into a neighbourhood park, complete with a kids’ play zone. Poetic justice, perhaps, carved in colourful rubber tiles. But if he refuses to comply, the civic body isn’t without recourse. They can legally attach his other movable property and auction it off to recover removal costs. That route is messy, sure, but it’s absolutely legally open.

Meanwhile, the Lok Sabha ethics committee could also take cognisance of the matter; no MP, after all, enjoys legal protection against findings of civic encroachment. Political analysts are already predicting that the opposition might just raise this issue in the upcoming winter session of Parliament, potentially turning a local land dispute into a much broader, national rule-of-law debate. For Yusuf Pathan, the clock is ticking, loudly. Four weeks can vanish faster than a yorker delivered at 150 kilometres per hour.

Lessons for Celebrities

Want to build a gym, a sparkling new pool, or even just an extended garden room? Here are three basic rules, not just for celebrities, but for everyone. First, check the land use on the master plan. Always. Second, apply through the proper, official channels. And third, wait for written approval. If the answer is no, take it on the chin. Seriously, no midnight walls, no flimsy “demarcation” theatrics.

Second, stop treating municipal clerks as glorified peons. These days, they work under digital dashboards that meticulously log every single file movement. There’s a paper trail, or rather, a digital trail, for everything. Third, and perhaps most importantly, remember your Brand Equity. A decade of goodwill, built on cricketing triumphs and public adoration, evaporated for Pathan in a single, damning headline: “encroacher.” For influencers who monetise their reputation, legal compliance is always, always cheaper than hiring an army of reputation-management agencies.

Finally, use your clout positively. If you genuinely need extra space, lease private property at market rent. It keeps you drama-free and, crucially, sets the right template for your millions of followers. The law isn’t some abstract opponent; it’s the umpire. Argue with the umpire, and you walk. Simple as that.

Broader Impact on Land Jurisprudence

This judgment isn’t just making waves in Gujarat. Courts in Bombay, Madras, and Kerala are already quoting Justice Bhatt’s clear, concise reasoning to fast-track other celebrity encroachment cases. Lawyers are already calling it the “Pathan precedent.” The key takeaway, the one that’s now ingrained, is this: a willingness to pay simply cannot cure illegality, especially when public land is involved.

This order significantly buttresses the constitutional promise of equality under Article 14 and strengthens the hands of municipal corporations under Section 308 of the Gujarat Provincial Municipal Corporations Act. Activists are hopeful it will finally discourage those dubious “regularisation” bills that some states are notorious for floating just before elections. Urban planners, meanwhile, see it as a much-needed nudge for transparent land banks and mandatory auctions. If the Supreme Court upholds this ruling, expect similar crackdowns on those sprawling farmhouses, fancy resorts, and lucrative wedding venues that have, for too long, sat illegally on riverbeds and forest edges. One small plot in Vadodara might just reset the entire national conversation on land as a public trust.

Conclusion

So, is anyone truly above the law? The Gujarat High Court just answered that question with a firm, resounding “no.” Yusuf Pathan’s episode is a stark reminder that reputation and votes might earn you headlines, but they certainly don’t earn you exemptions. If the Supreme Court sides with Justice Bhatt, and many legal experts believe they will, this message will echo from Mumbai’s bustling shoreline to Bengaluru’s encroached lakebeds.

What do you think—did the court get it absolutely right, or is it unfair to single out a star? Drop your view in the comments below. If you learned something new today, hit that like button and share this with friends who still might believe fame is some kind of impenetrable shield. For more stories where the law meets real life, subscribe and turn on notifications. Because in India, the gavel can spin faster than a cricket ball—and no one, not even a World Cup hero, can truly predict its swing.